WINNER: Bronze Medal, Best Book in Performing Arts, from The Independent Publisher Book Awards

www.ippyawards.com

www.ippyawards.com

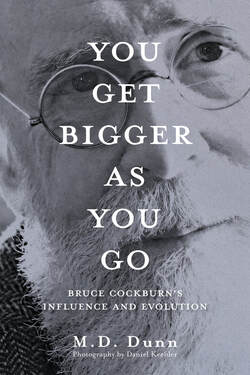

You Get Bigger as You Go: Bruce Cockburn's Influence and Evolution was written over seven years. It includes original interviews with: Bruce Cockburn, Bernie Finkelstein, Hugh Marsh, Eugene Martynec, Jonathan Goldsmith, Colin Linden, Don Ross, Stephen Fearing, Linda Manzer, and representatives from Oxfam and SeedChange. A song-by-song/album-by-album review section brings fresh perspectives to Cockburn's catalogue, tying it into the times and larger themes.

From the back cover:

Bruce Cockburn has enthralled audiences with his insightful lyrics and innovative guitar playing for over half a century. Hit songs like “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” “If I Had a Rocket Launcher,” and “Lovers in a Dangerous Time” are just part of the story. In You Get Bigger as You Go: Bruce Cockburn’s Influence and Evolution, musician and writer M.D. Dunn takes the reader on a humorous and obsessive quest to track Cockburn’s significant cultural footprint. Interviews with producers, musicians, activists, fans, as well as Bruce’s career-long manager, the legendary Bernie Finkelstein, and with the enigmatic Mr. Cockburn himself form the core of this critical assessment and appreciation. In these conversations, Cockburn and friends celebrate a life of music and social engagement.

You Get Bigger as You Go: Bruce Cockburn’s Influence and Evolution is the perfect beginner’s guide to the music and the artist, and a fun addition to any fan's library. Photographs from archivist Daniel Keebler span decades and show Cockburn in his natural habitat, on stage and in studio.

TO ORDER:

Ask your favorite independent bookseller,

or:

Amazon Canada

Amazon USA

Amazon UK

Amazon Australia

Amazon Japan

Amazon India

Amazon Germany

Amazon France

The print edition includes b&w photos by Daniel Keebler.

The ebook edition includes the b&w photos by Daniel Keebler

and colour album covers.

Direct order options for libraries and bookstores are available through the Ingram Content Group.

Ask your favorite independent bookseller,

or:

Amazon Canada

Amazon USA

Amazon UK

Amazon Australia

Amazon Japan

Amazon India

Amazon Germany

Amazon France

The print edition includes b&w photos by Daniel Keebler.

The ebook edition includes the b&w photos by Daniel Keebler

and colour album covers.

Direct order options for libraries and bookstores are available through the Ingram Content Group.

The book launch for You Get Bigger as You Go: Bruce Cockburn's Influence and Evolution was a grand time. We gathered at the Sault Ste. Marie Museum in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada to listen to some of Bruce's music and talk about the many ways his music has enriched our lives. Then, Bruce joined us for a Q&A session. The audio is a little squawky in parts. Hope you enjoy.

FIRST WEEK REPORT:

You Get Bigger as You Go Tops Folk and Country Musician Biography list on Amazon.ca

An excerpt from You Get Bigger as You Go: Bruce Cockburn’s Influence and Evolution by M.D. Dunn

with photographs by Daniel Keebler, coming soon from Fermata Press.

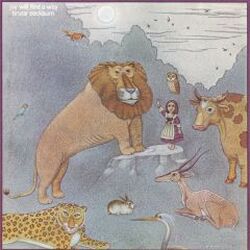

In this short, personal essay, Dunn writes about Bruce Cockburn's sixth studio album, Joy Will Find a Way, and how music can be a guide. This is by far the most personal passage in the book.

with photographs by Daniel Keebler, coming soon from Fermata Press.

In this short, personal essay, Dunn writes about Bruce Cockburn's sixth studio album, Joy Will Find a Way, and how music can be a guide. This is by far the most personal passage in the book.

Joy Will Find a Way

Released 1975

True North Records, TN-23

Eugene Martynec, producer

Blair Drawson, cover image

Bart Schoales, art direction

Joy Will Find a Way, released in 1975 and produced by Eugene Martynec at Toronto’s Eastern Sound Studios, finds Cockburn travelling, thinking about love, and exploring the potential of his recently declared Christianity. He is also thinking about politics, specifically U.S. interventions in Latin America. But at this point, these matters were theoretical.

Everyone has a point of introduction with Bruce Cockburn’s music, and Joy Will Find a Way is mine. Since I have lived with it the longest of any Cockburn albums, there is much to say. Casual fans often think their first Cockburn album is the first Cockburn album. I have met people who have come on board with 1983’s Stealing Fire, Bruce’s thirteenth studio album and one of the commercial high points in his fifty-plus years of record-making, saying things like, “I loved his first album, the one with “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” on it, but haven’t heard any new stuff.” I was kind of the same way with Joy Will Find a Way, which I found at the age of fourteen, about eight years after its release. It never occurred to me to search for albums before that time. The cassette copy I rescued from the discount bin appeared like a miracle, and one shouldn’t question miracles.

Other artists with decade-spanning catalogues likely share the experience of being constantly discovered. Like North America to Columbus, the music already existed before the listener became aware of it.

There were no liner notes in the cassette copy I’d found, and no picture, just the playful scene on the cover by Blair Drawson, which is a wonderful surname for an artist, depicting an unlikely gathering of predator animals, a lion and cheetah, with a long-horned gazelle, cow, rabbit, owl, heron, and various songbirds. Standing on a tree stump, reaching one hand toward the lion’s mane, is a little girl wearing a pinafore apron over her dress and a bow jabot to complete the ensemble. All eyes look toward the audience, like the figures are enacting a tableau. In the background, clouds or mountains bounce along the horizon with birds rising to the sky. Drawson also provided the cover image for Cockburn’s 1984 album Stealing Fire. The images for these albums are so different in style, it is difficult to recognize the same artist’s hand. Currently an instructor at Toronto’s Ontario College of Art and Design University, where he teaches book illustration, Mr. Drawson says he remembers he was “painting the floor of my studio at the time. And there was Bart [Schoales] calling to say the cover had won the Juno.” Schoales is another artist and graphic designer who worked on many album packages for True North and several for Bruce.

Truth be told, it really was the image on Joy that attracted me to the cassette. Cockburn’s name meant little to me at the time of that first discovery, but Drawson’s painting stirred childhood memories of Cat Stevens’ Teaser and the Fire Cat and Tea for the Tillerman albums. That liminal age between childhood and teen years is a vital time in a person’s musical life. At fourteen — or thereabouts — childish games and notions cling like bits of busted-through shell while we test new depths and farther fields. Thoughts of work, sex, and the desire for independence begin to enter the mind of a young teenager. It’s a time to stand with one foot in childhood and the other in adolescence, a time when small things can establish lifelong trajectories. For me, it was the fear of darkness and my devotion to Roman Catholicism that began to dissolve right around the time that Joy found its way into my hands. I had begun to break from the dogma of the church, which I had believed with complete devotion. All of it. But lately, mass had become a ritual of “sit, stand, kneel” and little else, and I began to see something unnerving in the priest’s eyes. And Cockburn’s music played a part in this awakening, although in an unusual way.

Joy Will Find a Way opens with a slow love song titled “Hand-Dancing.” The song’s title could describe the guitar playing on the album as well, which continues Cockburn’s exponential development on the instrument. Lyrically, “Hand-Dancing” is minimalist, made of only three lines: “Song swaying in the air / I’m hand dancing in your hair / You’re hand-dancing in my soul.” The guitar keeps a Cockburn-type rhythm: plenty of accented stops and muted string strikes punctuated with blindingly fast runs of notes. The main guitar solo in the song seems to be drawn from classical, perhaps Mediterranean influences.

“January in the Halifax Airport” finds Bruce in narrative mode, describing, as promised in the title, scenes of travellers in the Bardo between destinations. Airports are places out of time, a nowhere zone. Some travellers enjoy the neutral, liminal ground, while others find it intolerable. People in these timeless spaces, like elevators and airports, either cocoon themselves in distraction or sleep or let it all hang out. Unless one has a decent book or a good Wi-Fi connection, there can be little to do but observe people and reflect on one’s place in life. The speaker in “January in the Halifax Airport Lounge” is making big observations in a confined space. Noting the “crisis in the outer world,” the narrator contemplates the busy-ness of modern existence, concluding each verse with a line of longing, perhaps for a lover, perhaps for God.

Bruce played two shows at the Writers at Woody Point Festival in Woody Point, Newfoundland in 2015. Woody Point is a small community on the west coast of the province, in the middle of the magnificent Gros Morne National Park, a sprawling 1,805-square-kilometre tract with some of the most primitive and awe-inducing landscapes on the continent. The concert was held in a lovely venue then called the Heritage Centre Theatre. Later that year, its name was changed to the Shelagh Rogers Theatre to honour the long-time host of CBC’s flagship literary program The Next Chapter. Built in 1908, the hall originally functioned as the Orangeman’s lodge. After considerable community effort, the building was transformed into a 150-seat capacity concert and dance hall with a large open space upstairs.

After the concert, Bruce sat alone at a foldout table, a glass of red wine beside him and felt-tipped markers scattered around. We shuffled forward as the line grew behind us, along the walls and out the door. Everyone in that room had a connection to Bruce through his music. And some had other connections. One man had taken Bruce on a canoe trip thirty years before. The man’s wife introduced the two. “Do you remember?” Bruce looked at the man, and yes, he did. The entire room leaned in to hear Bruce talk with the canoe guide, a man too shy, it seemed, to say much.

Our turn was next. I didn’t know what I was going to say. I’d packed the album jacket of Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws, hoping he’d sign it, which he did.

Along with the album jacket, I’d brought copies of my first and third poetry collections, Ghost Music and Even the Weapons, as gifts. It hadn’t occurred to me that others would be making offerings as well. Small boxes, bags of mysterious objects, and stacks of books were

mounting up on the table around him. “Here, Mr. Cockburn, if you’d like…these are two of my books,” I said. He reached out with both hands and drew them in.

“Yes. I do like,” he said.

Then it was time for me to say my piece. I was stammering a bit, although I don’t know why. He is usually one of the calmest, most inviting people you can imagine. There is nothing showy about the man. But when he engages with you, he is all there, and that can be intimidating in an age when people pay half-attention with part of their minds waiting for a cellphone’s siren buzz.

“Your music has made me a better person,” I said. “My life is better for having known your music.”

He let out a long sigh at that point, as if I’d told him he held up the sky, and he pushed his hands across the table toward me in the opposite motion with which he’d received the books. The gesture said everything: I cannot accept that responsibility.

He didn’t say that, of course. Instead, he said, “That is very kind of you to say. I am glad my music has a place in your life.”

Then he signed our album, and we moved along.

What I said to Bruce Cockburn that first time we spoke was true. His music has changed my life. Not just his music. Music in general has changed my life. Hasn’t it changed yours? Music has made life more livable, given insight into situations I thought untenable. In times of confusion, frozen in fear and indecision, if I listen closely, lyrics from songs I’ve loved will bubble up from my unconscious, arriving to guide me through the dark wood. I picture the unconscious mind like a DJ sorting through a nearly infinite catalogue of songs the brain has stored away, looking for the perfect reflection of the moment.

What I didn’t tell Bruce Cockburn was that at a crucial moment a line from one of his songs steered me toward life. A path led to marriage and community while I was leaning toward uncertainty with an eye on desolation. I might have left town and walked away from what has been one of the most important relationships of my life had the internal DJ not spun a lyric from Bruce’s song “Starwheel” one evening:

We’re given love, and love must be returned.

That’s all the bearings that you need to learn.

See how the Starwheel turns.

“Starwheel” was cowritten with Bruce’s first wife, Kitty, who shares a writing credit. As the line from that song wafted up from my subconscious, I didn’t know any of that. In fact, I hadn’t thought of the song for many years, but I heard it, plainly, cutting through clutter: “You’re given love, and love must be returned.” The line had stayed with me, waiting like a seed for over a decade.

It is not an original thought, perhaps. George Alexander Aberle, better known as eden ahbez, expressed a similar plea to reluctant lovers in his song “Nature Boy,” which was recorded by and became a monster hit for Nat King Cole in 1948. Ahbez, writing twenty-eight years before “Starwheel,” ends his song about the “strange, enchanted boy” with the realization that the exchange of love between people is the most important lesson one can ever learn. Had I been more into Nat King Cole in my early teen years, that line might have been the nudge.

This is the process of art reception: interpretation, integration, influence. Our relationship with Bruce Cockburn’s music has nothing to do with Bruce. Our relationship with the art that influences us bypasses the artist. I have never told Cockburn how a song he and his ex-wife wrote on my sixth birthday helped to change the course of my life for the better. It’s none of his business, really. For all I know, the line that so influenced me may have been written by Kitty, not by Bruce. Maybe I stood at the wrong table and thanked the wrong person.

The artist is simply the messenger. And the song did not change my mind; rather, it revealed what had been hidden.

The lyrics for “Lament for the Last Days,” the fourth track on Joy Will Find a Way, could exist on the page as a poem. That is not true for most song lyrics. Most songs don’t scan well when read. “Lament” is just that, a slow, lilting melody — not maudlin, but aware of endings — that reminds the listener of the seemingly slow progression of days that ends all too soon.

The title song, “Joy Will Find a Way (A Song About Dying)” is one of the peppier tracks on the album. It is lyrically minimalist, made of two quatrains, which Cockburn accompanies on a dulcimer. The song is a celebration of life and transition:

Make me a bed of fond memories

Make me to lie down with a smile

Everything that rises afterward falls

But all that dies has first to live

As longing becomes love

As night turns to day

Everything changes

Joy will find a way

“Burn” is the first indication in Cockburn’s recorded music of his interest in Latin American politics. He had yet to travel to Central America, but, influenced by his brother Don, who was involved in humanitarian work in Nicaragua, and the writings of Ernesto Cardenal, Cockburn was growing toward a deeper engagement with these issues and the people struggling under American imperialism and rogue dictatorships. “Burn” is told from the perspective of a person observing the arrival of a “Yankee gunboat.” But U.S. military presence is not the cure many hope for: “Come tomorrow, we all gonna pay / And it’s burn baby burn / When am I going to get my turn.”

“Skylarking” is three minutes and twenty-five seconds of instrumental glory that nearly killed me. I had never heard a guitar played like that before, which is something many listeners say upon first hearing Cockburn’s music. Accompanied by hand percussion that stumbles a bit to keep up, the piece is written in an alternate tuning that makes it sound like multiple guitars played simultaneously. Typically, a guitar is tuned EADGBE, from the lowest to the highest string. Each fret changes the pitch of the note by a half-step, a sharp or a flat, with the exception of the E to F and B to C intervals, which are half-steps away from each other anyway. At fourteen, when I discovered Joy Will Find a Way, I could barely manage to keep my guitar in standard tuning. It had not occurred to me that the instrument could be tuned in any other way. For that first year, the strings were more likely to break than to come into pitch when I cranked the tuning keys.

So, listening to “Skylarking” for the first time, I heard no similarity between the sounds from the speaker and the sounds from the acoustic guitar in my lap. First of all, there are few chords in the tune. Most songs are structured from set patterns of chords that repeat in predictable ways, and learning songs up to that point involved memorizing chord progressions.

“Skylarking” is built around three patterns of notes, movements really, with Cockburn soloing over the main rhythm with precision, speed, and enviable tone to make the sky reel. The rhythm is applied underneath the flurry of notes with Cockburn returning to the main part at the end of each cycle. I had listened to classical players like Canadian Leona Boyd, who seemed to be on every television program in the 1980s, and Andrés Segovia, the Spanish guitar master. The music they played was beyond me, but it was supposed to be; it was classical music, after all. And I had marvelled at Roy Clark’s flatpicking every week on the camp-country TV variety show Hee Haw. “Skylarking” wasn’t classical music, and it wasn’t country or rock either. It was a style of guitar playing that was alien to anything I had known. It was music the gods might play in their celestial palaces. It was music from a distant planet populated by geniuses.

Joy also contains one of the loveliest love songs in Cockburn’s catalogue. “A Long-Time Love Song” recounts a relationship that spans a lifetime. It’s a beautiful meditation on love tempered by time and experience.

With “A Life Story,” the longest song on the album, Cockburn recounts the birth and resurrection of Jesus Christ in twelve lines of verse. Basically, “Christ is born for you and me,” “Christ is nailed upon a tree,” and “Christ is risen to lead us free.” It is by far the most literal Christian-themed song released to that point.

“Arrows of Light,” the closing track, has become a standard at Bruce Cockburn concerts in the 2020s. Played on a dulcimer, the song is another celebration of life, of music, of community. In concert, it rings out like a prayer. Hearing it performed live can be a moving experience, a reminder to take no aspect of life for granted. After all, as the song goes: “Life is singing.”

Excerpt from You Get Bigger as You Go: Bruce Cockburn’s Influence and Evolution (Fermata Press). © 2023 Mark David Dunn/Feathermoon Musical Productions

COMING SOON:

You Get Bigger as You Go: Bruce Cockburn's Influence and Evolution

by M.D. Dunn with photographs by Daniel Keebler (Gavin's Woodpile) and interviews with dozens of musicians, producers, fans, as well as original interviews with Bruce and his manager, the legendary Bernie Finkelstein.

An excerpt from an interview for You Get Bigger as You Go: Bruce Cockburn's Influence and Evolution. In this clip, the incredible musician and composer Hugh Marsh, who has worked with Bruce Cockburn since the mid70s, speaks about Bruce's importance as a lyricist and that mind-melting solo on "Loner." It's all in the book, coming soon from Fermata Press.

Unless otherwise noted, all material copyright 2023 Mark David Dunn/Feathermoon Musical Productions

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by Web Hosting Canada